Tax alpha – what is it, and why should you care?

It’s All About How Much You Keep

When it comes to return on investments, it is not about how much you make but how much you get to keep. This post will explore that notion. It will not go in depth on the complexities of taxes and how they affect investments, but rather offer an introduction as to why taxes are important when investing. Looking at your portfolio’s total return without taking taxes into consideration can have dramatic financial planning consequences.

An example: Ben is an investor saving for retirement. His initial investment is $250,000. Assume a holding period of twenty-five years, an average annual return of 6.5 percent and a capital gains tax rate of 20 percent.

After twenty-five years Ben’s portfolio has a total value of $1,206,924.78:

![]()

Of this total value, $956,924.78 are capital gains:

![]()

Those capital gains are taxed at our hypothetical 20 percent, meaning Ben has to pay $191,384.96 in capital gains tax when he sells and withdraws money from his portfolio at the end of twenty-five years.

![]()

The total amount that Ben gets to keep is $1,015,539.82.

This example is not completely realistic, but is a useful illustration. Ben’s total portfolio return before tax is 383 percent while his total portfolio return after tax is 306 percent. This is a huge difference. Before he sold his positions and withdrew money he might have looked at his statement and thought he had slightly more than 1.2 million dollars available to spend, but it is actually almost $200,000 less than that. Again, it is more about what you get to keep rather than what your portfolio earns that matters!

The question is now, how do we keep more? The key is tax efficient investment management and tax efficient financial planning!

Location, Location, Location

Asset location is a big way you can keep more of what you earn in your accounts. Asset location means that you are putting the correct investments into the correct accounts for tax efficiency. This means looking at the type of investment account and making sure the type of investments there are optimal.

There are seemingly countless savings vehicles in the U.S., and, depending on your type of work, you might have more or fewer options when it comes to opening accounts. Most investors can open an individual brokerage account – this “non-qualified” account is one where you may pay capital gains tax and dividend tax each year, based on the value of any trades you did or dividends received. Many might have access to a 401(k) account, a traditional IRA, or a SEP IRA. These are pre-tax or tax-deferred investment accounts, meaning you only pay tax when you withdraw money out of the account, not annually or for any changes inside of the account. Then you also have investment accounts like a Roth IRA or a Roth 401(k), where all earnings are tax free, with certain restrictions. This is by no means an exhaustive list of available account types; there are too many to list and cover in this blog.

It is pretty common to have more than one type of investment account, and there are a few rules of thumb you can use when it comes to asset location in them. If you have multiple accounts of different types (e.g. brokerage, 401(k) and Roth IRA) and those accounts have identical or very similar holdings, that almost surely means your accounts are not tax optimized. Different investments work better for different accounts. So if you have a mix of stocks and bonds in your portfolio, you might want to consider placing your high-turnover holdings (like mutual funds) and/or fixed-income holdings (like bonds and CDs) in a tax-advantaged, or “qualified,” account to lower your tax burden. Equity like individual stocks and ETFs might serve you better in a brokerage account.

Harvest Your Losses

Another way you could potentially lower your tax burden is by tax loss harvesting. Tax loss harvesting is selling an asset at a loss (on purpose) and then either immediately replacing the position with a different-but-comparable asset or waiting long enough to re-buy the original asset to avoid the wash sale rule. If done properly, this silly-sounding maneuver can allow you to maintain the same type of investment portfolio, but offset actual gains with paper losses to lower your tax bill.

You may have heard of direct indexing investing by now. Direct indexing is when you hold individual stocks or securities in an account that are meant to resemble some sort of index or benchmark, e.g. the S&P 500®, since those indexes or benchmarks are for reporting and not something you can purchase. Now, if you really wanted to hold the S&P 500® in your portfolio, you could purchase a mutual fund or an ETF that tracks the S&P 500® for you. However, if you wanted to hold the S&P 500® and benefit from tax loss harvesting you might want to consider direct indexing because it gives you control over individual investments.

With direct indexing it is important to do ongoing tax loss harvesting because opportunities for tax loss harvesting tend to diminish in the long run. Most assets have a long-term positive return, and there would need to be an incredibly dramatic drawdown in the market to cause a long-term return to go negative. In the short run though, asset returns move up and down a lot more often. When one of your holdings is relatively down, that is when you should capitalize on tax loss harvesting – capturing these movements adds up over time when it comes to tax savings. To learn more about how investment returns and volatility vary over different time horizons check out my previous post Risk: Time Horizons Matter.

Here direct indexing is only important to know as it pertains to tax loss harvesting. The example that follows is meant to illustrate how harvesting works and how it might benefit you.

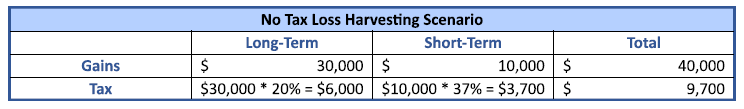

An investor named Sally is looking to withdraw $40,000 from her investment account to cover a large roof repair. Assume that the long-term tax rate for capital gains is 20 percent and that the short-term rate is 37 percent. (For the sake of fewer steps and a simpler explanation, I’m also ignoring cost basis, which is a pretty big factor in calculating real-world gains and losses.) Here is how those taxes would break down for Sally:

Sally sells $40,000 worth of investments and receives $40,000 of proceeds to pay for the roof. Sally will owe an additional $9,700 in taxes (but know that there is no automatic withholding for stock sales. Sally will need to pay this tax from other income or savings.)

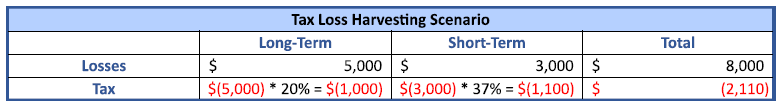

But what if Sally had taken advantage of tax loss harvesting opportunities in her account earlier that year? This is how that would affect her tax liability:

By using tax loss harvesting during the year, Sally offsets some of the long-term and short-term gains she realizes in that year. Tax loss harvesting will help her save $2,110 because she will only owe $7,590 in additional taxes (instead of $9,700 in a scenario with no tax loss harvesting). Sally can use these “paper losses” to improve her overall finances without upsetting the asset allocation of her portfolio.

Keep in mind that this discussion of tax efficiency, asset location and tax loss harvesting is not meant to be a how-to guide, just an outline of a few ways in which you might be able to keep more of what you earn in your investment accounts. If you are working with an advisor, ask them if these services are offered or if they are providing them for you. At Cardinal we provide tax sensitive financial planning and investment management, including direct indexing.

Anessa Custovic, PhD